Salt vs. Gold

The Intriguing History of the West African Salt/Gold Trade

Salt vs Gold

You’ve probably heard the oft-quoted fun fact: “Back in ancient times, salt was worth its weight in gold!”

But is it true?

The answer is a definite “maybe,” but only in very specific places under very specific circumstances.

Regardless of how true this claim is or isn’t, though, the history associated with it is pretty interesting.

Here goes.

In the early middle ages, trade started to develop in west Africa through the Ghana empire. Plenty of commodities changed hands, but the most important were salt and gold. Don’t let the name fool you, the present day nation of Ghana is a ways off from where the Ghana empire was.

The map below shows the pertinent places we’re talking about.

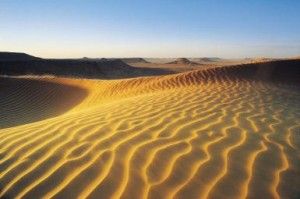

So if you were to head north from the Ghana empire, you’d soon find yourself in the middle of this:

Not much to see here.

But, in certain places in the Sahara, like Taghaza or Taoudenni, if you dug through a couple feet of sand, you’d hit halite deposits (salt). So traders from north of the Sahara started crossing the desert to trade with the people south of the Sahara. Among other things, they were interested in gold.

Conveniently, the people from Bambuk region, west of the Ghana empire, as well as the people from the Wangara region, south of the Ghana empire, had lots of gold. But wouldn’t you know it, they were a little short on salt. You see where this is going.

Pretty soon, Arab traders set up salt mining operations in Taghaza and Taoudenni. They brought in slaves, and left them there to get blocks of salt ready to load on their caravans when they rolled in from the north. Since there was literally nothing in these places except for salt, water, and sand, they brought in all the food for the slaves on these caravans. They lived on dates, camel meat, millet, and of course, all the salt they could eat. Once the caravan left, there was no need to worry about the slaves running away, they had the only food and water for many miles in any direction. They even built their houses out of salt because there was nothing else to build with.

The Ghana empire ran a tight ship when it came to commerce. They policed their travel routes to provide traders a safe strip though their territory (in exchange, of course, for some hefty duties levied and everything going in and out of their borders.) So if the Arabs traders could make it through the Sahara, it was then smooth sailing to get to the Bambuk and Wangara regions where the gold was.

But once they got there, instead of meeting face to face and haggling, they engaged in silent barter, which is exactly what it sounds like. Nobody says anything, and often the parties don’t even see each other.

It often went more or less like this: The Arab traders show up at a designated trading location. They lay out the salt they want to trade. Then they beat on some drums so that the Wangarians know they’re ready to trade, and they withdraw back to wherever they’re camped out, a fair distance away, but within earshot of drumbeats. The Wangarians show up, take a look at the salt, and then put a pile of gold next to it that they think is a fair price. They then beat on some drums and withdraw from the trading location. The Arab traders come back, check out how much gold the Wangarians have left, and decide whether or not it’s enough. If they’re satisfied, they take the gold, leave the salt, beat on their drums, and leave. If they want a higher price, they leave everything, beat on their drums, and head back to camp, so as to give the Wangarians a chance to offer more. The process continues until a deal is reached.

This process sounds a little strange, but it served a couple of purposes. First, language differences were no barrier because speech simply wasn’t used. Perhaps more importantly, it ensured that no trade secrets slipped out. For example, the Wangarians traders kept the locations of the gold mines strictly secret to prevent the Arabs from simply bypassing them and going straight to the gold. It is said that if a miner was captured by traders, he would die before revealing the location of the gold mines. One story holds that a miner was captured and killed in an effort to discover the location of the mines, and when the Wangarians found out about it, they refused to trade for 3 years as retaliation. When you are that serious about keeping something secret, the less direct human interaction the better.

So this brings us to our original question. Was salt traded, pound for pound, for gold? Wikipedia thinks so. Under the topic “Silent Trade,” it says:

Also in West Africa, gold mined south of the Sahel was traded, pound for pound, for salt mined in the desert.

This sounds doubtful, given that salt was so plentiful in Taghaza that they used blocks of it to build houses, whereas the Wangarians had to work hard to obtain relatively small quantities of gold. (They certainly weren’t making gold cinder blocks.) Also, while salt wasn’t plentiful in the Wangara and Bambuk regions, it did exist there.

On the other hand, shipping and handling fees on blocks of salt all the way from Taghaza were steep. One traveler from the late middle ages noted that the price of salt quadrupled between the northern edge of the Ghana empire and an area just north of the Wangara region. And that was the easy part of the trip. The other half of the journey was through the Sahara.

Still, I tend to agree with Mark Kurlansky, the author of Salt: A World History. His take:

It was said that in the markets to the south of Taghaza salt was exchanged for its weight in gold, which was an exaggeration. The misconception comes from the West African style of silent barter… From this it was reported in Europe that salt was exchanged in Africa for its weight in gold. But it is probable that the final agreed-upon two piles were never of equal weight.