Photo Blog

Learn about things you won't find in a tourist guidebook.

How to Plough in Las Alturas

How to Plough in Las Alturas

At lower altitudes in the Sacred Valley Region, common draft animals like bulls or oxen are put to work plowing the fields. For wide open, flat fields, small tractors are also used. In las alturas, though, things are very different. At 13,000ft, draft animals can’t cope with working in the thin air, and low crop yields (also, owing largely to the cold, thin air) do not justify the expense of investing in machinery. So instead, the chaki taqlla is the sod-breading instrument of choice. This clip was taken near Ccelcanca, about a three and a half hour drive into the mountains above Ollantaytambo.

Narrow-Gauge Bypass to Machu Picchu

Narrow-Gauge Bypass to Machu Picchu

This picture was taken a little downstream from Piscacucho, which is far down the Urubamba River as you can go by road. For those that are too cheap to pay the $50USD (and up) each way to ride the train to Machu Picchu, or the hundreds of dollars to hike the Inca Trail, there is a third option: Walk a trail that begins in Piscacucho and follows the railroad tracks for 29 km down to Machu Picchu. Not only can you feel smugly self-satisfied for refusing to support the foreign-owned rail company that gouges tourists without benefiting local residents, but you can also enjoy a series of great views like this one. Just be discreet, as this is sternly frowned upon by the railroad folks. Nothing makes a self-satisfied smirk disappear more quickly than being told “You can’t walk here,” and being forced to return the way you came. Whether or not they technically have the authority to tell you this is pretty foggy, but it doesn’t make much difference - you have to go back.

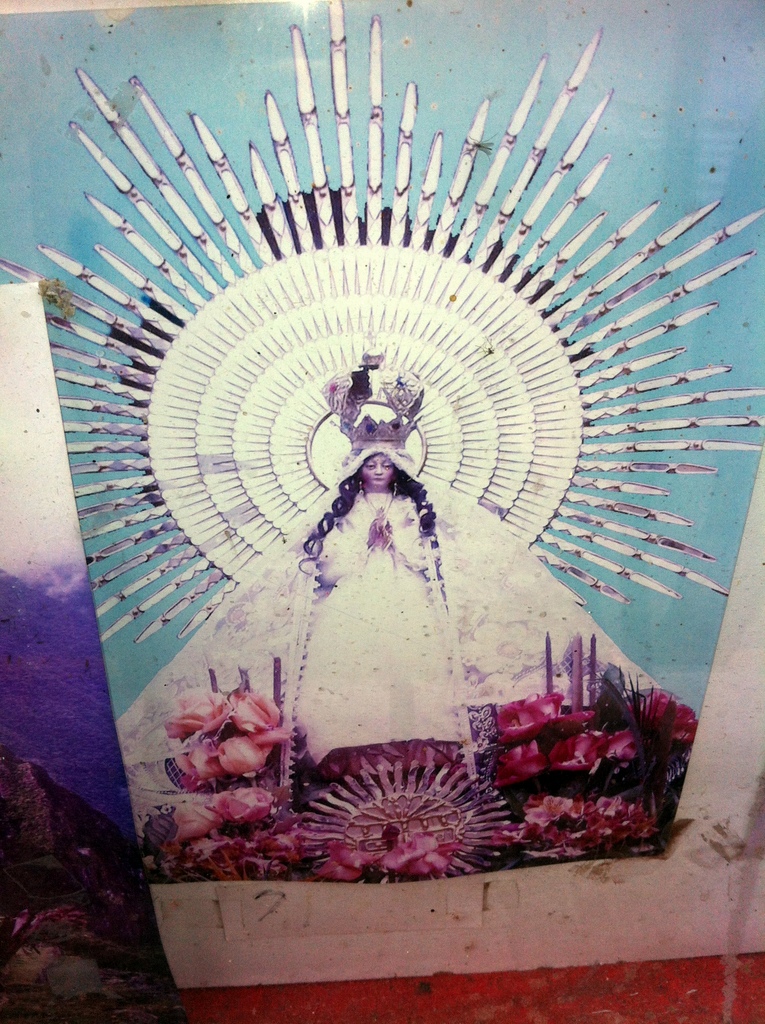

Santa Maria (aka Pachamama)

Santa Maria (aka Pachamama)

One of the deities most revered by the ancient inhabitants of the Sacred Valley Region is Pachamama: Mother Earth. (Yes, you did notice correctly that mama is Quechua for “mother.” This is something that all kinds of seemingly unrelated languages have in common.) This adoration was characterized by the worship of the mountains of the region. As the Catholic Church moved in on the tails of the Conquistadores, the clerics asked themselves how best to “reach” the natives with the true faith. Apart from the typical mixture of carrots and sticks (mostly sticks) one strategy was to mesh the local worship with the Catholic tradition. Who could better mesh with the mother earth goddess worshiped by the natives than Mary, the mother of Jesus? Much of the religious art of this era consequently features Mary looking a lot like an Andean mountain. Incidentally, right up to the present time, whenever an alcoholic beverage is drunk, the first little bit is poured on the ground as tribute to Pachamama. It is also standard practice to pour out an offering to Pachamama when breaking ground to build a new home. I was chatting with the proprietor of a store once, and a man bought a soda to take to his property to offer to Pachamama, since they were about to start construction. A few minutes later he came back and asked the owner if he could return the plastic soda bottle he bought and buy a glass one instead. Why? “Pachamama doesn't like plastic.”

Stray Dogs

Stray Dogs

All cities, towns, and villages in Peru have stray dogs that wander the streets. Most of the time they are a health hazard, spreading disease and parasites, and sometimes even forming aggressive packs. Sometimes though, their habits can be endearing, as with these three. For the better part of a year, I would hardly ever see one of these guys around Urubamba without the other two. They just seemed to like to be together. Here they are curled up next to their favorite adobe wall on a cool June morning (June is typically the coldest month here) at about 6:00 a.m.

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

Although labor is cheap in rural Peru, many manufactured goods must be imported from more highly industrialized nations. Most imports are subject to high tariffs and are thus significantly more expensive than they would be in the U.S. This makes them unattainable for many. As a result, one commonly sees handmade tools like this hacksaw made from rebar. While the level of poverty is sobering, it is also impressive to see the drive to do what needs to be done overcoming the frequent obstacles that plague developing countries.

Room with a View

Room with a View

Just downstream from Urubamba, in the town of Pachar, hundreds of people drive along on their way to Ollantaytambo without noticing the tourist attraction overhead. If you happen to fix your gaze on the sheer rock cliff at a spot about 400 feet above the valley floor, you’ll see some egg-shaped polycarbonate structures just kind of hanging there. These pods comprise a breathtaking luxury hotel owned by Natura Vive, a company that also has a series of zip lines in the Sacred Valley area. For those who have the stomach to climb up and spend the night, you can enjoy a spectacular view of the lower end of the Sacred Valley. Staying in these pods is a bit above our pay grade, so we don’t have any photos of our own to show you. However, you can get a good look by visiting the following link: http://www.boredpanda.com/scary-see-through-suspended-pod-hotel-peru-sacred-valley/

Livestock vs. Pets

Livestock vs. Pets

Most rural Peruvians are petty pragmatic in their approach to life. Animals are typically kept for wool or food – not for company. Try telling that to this little guy, though (photo taken near Urubamba). You’d have to look long and hard to find a culture where children don’t like being with their animals.

Descending from Abra Malaga

Descending from Abra Malaga

As you descend from Abra Malaga (Malaga pass) into the Sacred Valley, you start running into settlements at about 13,500 feet. Alpaca do better at altitude than cattle, but it is not uncommon to see sheep as well. Although people here are indeed quite isolated, the government makes sure that all of them have at least a radio and small solar panel to charge it so that they can hear important news announcements.

Altitude is Relative

Altitude is Relative

Many think of Machu Picchu as some kind of mystical ruins high in the Andes mountains where the weather is freezing cold and only the strong survive without oxygen. Actually, this is not true. The capital of the Incan empire was Cusco. It is situated at about 11,500 feet and can get rather cold (from April to October temperatures regularly fall well below freezing at night). Thus, Incan emperors often wished to vacation to a warmer area where they could relax and host visiting dignitaries in comfort. Their “Camp David” was Machu Picchu. At less than 8,000 feet elevation and about 13 degrees south of the equator, Machu Picchu is quite comfortable year-round and rarely causes tourists to have trouble breathing. This picture is taken from one of the nearby mountains looking down on Machu Picchu.

Guaranteed for 30,000 miles

Guaranteed for 30,000 miles

This young man that has come down from the alturas to Ollantaytambo to go to the market. Notice his footwear. Ojotas like his typically cost between 3 and 5 USD and are made from the tread of old tires. They are worn all day, every day, for years on end before eventually failing. I have found that ojotas are very hard to break in, producing all kinds of blisters within an hour of putting them on. With time though, if you manage to survive wearing them long enough, you will find them to be the most rugged and durable sandals that money can buy.

Altitude is Everything

Altitude is Everything

With most of the Sacred Valley being above 10,000ft elevation (and the surrounding areas only going up from there), the inhabitants are definitely affected by the altitude. One obvious effect is that many animals (and even some people) look pretty barrel-chested at birth. This puppy is a good example. Another effect common in people is high blood pressure. More red blood cells make blood more viscous and viscous blood requires higher pressure to move it through the capillaries. Many who aren’t native to the region also note difficulty with digestion, shortness of breath, and even depression over the long term.

Teamwork

Teamwork

This short video was taken in Willoc a small village at about 12,000 ft elevation, 30 minutes outside of Ollantaytambo, located on the northwestern end of the Sacred Valley. Nearly all homes in rural areas here are constructed with adobe, but some local builders are beginning to experiment with metal studs and drywall. As is so often the case in small rural communities, neighbors will help each other when needed. As there are no roads that climb to the upper end of Willoc, these residents must haul all of their building materials by hand about 500 yards up a very steep hill in order to build. Most mothers do just about everything with a baby on their back.

Building a House with no Nails

Building a House with no Nails

Ever wonder how people built houses before nails were invented? Many times, they did it the same way people still do in rural parts of the Sacred Valley. This picture was taken in the small village of San Juan. San Juan is a 3.5 hour uphill walk out of the town of Yucay which lies between Urubamba and Calca in the Sacred Valley. Thanks to the decay of the thatching on this roof we can to see the basic structure. First, the adobe blocks are stacked to make the four walls. Then adobe blocks are stacked to form a triangle shape on two opposing walls. Branches are then laid across these opposite triangles, followed by thatching on top of the branches. For extra security the branches may be tied down to studs that are set into the adobe walls. The result is a simple, rectangular, rainproof home without any iron fasteners.

The Old and the New

The Old and the New

Historically, residents in the high altitudes surrounding the Sacred Valley have used llamas as pack animals and for meat while using alpacas for wool and meat. While, some still use llamas in the very rural areas, especially when there are no roads nearby, most people are finding it easier to use motorcycles for small loads. Alpacas however have not been replaced. Lots of the local clothing is still handmade from alpaca wool and alpaca meat is the staple protein supply in high altitudes. This young man’s poncho is obviously handwoven in the typical style worn in Patacancha and surrounding villages above Ollantaytambo on the northwestern end of the Sacred Valley. He is most likely carrying a variety of potatoes in the large sack, and one can observe alpaca grazing on the hill in the background. The altitude here is around 14,000 ft.

Read Those Warning Signs!

Read Those Warning Signs!

One bridge crosses the Vilcanota River into Urubamba from Cusco. About three years ago, two trucks loaded with sand and going opposite directions passed each other on the bridge. Fortunately they made it off the bridge before it collapsed altogether, but not before it was severely compromised structurally. Notice the steel I-beam along the top of the bridge crumpled slightly. The handrails along the side of the bridge show just how much distortion the bridge suffered. Needless to say, the bridge was immediately closed and repair work began. Incredibly, within a week there were two temporary bridges installed (one going each way) that allowed ordinary traffic to resume between Urubamba and Cusco. People started to get used to these temporary bridges, so, they became more or less permanent, and are still being used to this day. This picture also offers a good example of how women tend to dress in the Sacred Valley. This style of hat is very common due to the intense high altitude tropical sun. Almost all women, (and many men as well, wrap babies, groceries, tools, or whatever else they might want in the brightly colored Qéperina slung across their backs.

Syndicated Tricycle Union

Syndicated Tricycle Union

In the Sacred Valley region, if you want to participate in any kind of a trade, you have to be part of a union. Here you can see a triciclo proudly displaying his placard indicating that he is part of the Associación de Triciclos. (By the way, if you need to move heavy stuff, like sacks of rice, around the center of any town, triciclos are pretty quick and inexpensive.) In many cases, it is either illegal or an invitation for extra-judicial retaliation to try to participate in a business without being part of the appropriate union. While on some levels the local trade associations attempt to provide what people typically expect from unions, (political leverage, economic leverage, better wage stability) most of the people that I have talked to are very dissatisfied with both the methods and results. For starters, there are frequent mandatory meetings for all members and stiff fines for those who do not or are unable to attend. The unions are also constantly going on strike. Many times, the majority of the members don't even know why the strike is taking place. Sometimes, the strike has no said purpose other than to “show the power of the union and call attention to its importance.”

Don’t Forget Your Lucky Underpants!

Don’t Forget Your Lucky Underpants!

In the month of August, the entire Sacred Valley becomes very windy with the changing of the seasons. The locals view this as a changing of fortunes and try to make the most of the opportunity. It is thought that wearing red underwear will help you with your love interests and yellow underwear will give you general good luck. Fortunately, there is an abundance of local venders to fill this urgent need.

They Don’t Make ‘em Like They Used To

They Don’t Make ‘em Like They Used To

This picture was taken in Q’akllarakay, in the Maras region. Nearly every family in the vicinity raises at least a couple of pigs. Of course, livestock need feeding and water troughs. Those typically used around here are made from solid stone. Grandpa or great-Grandpa hewed them out decades ago. (Apparently the old Inca habit of shaping stone for anything and everything still runs strong in the veins of their descendants.) A few early-adopters have attempted to modernize by switching to plastic containers for their feeding troughs. But they soon regret it. The sun here, at a subtropical latitude and very high altitude is intense and, before long, the plastic trough is reduced to brittle plastic shards.

When Life Gives You Potatoes. . .

When Life Gives You Potatoes. . .

In the high altitudes of Peru, most people live almost exclusively off of potatoes with a little bit of alpaca meat thrown in for protein. Although this is not the most varied diet one could think of, they have managed to conjure up a great deal of variety in preparing and preserving their potatoes. Some of the most common ways are to make chuño or morayah. Basically this involves allowing the potatoes to freeze and thaw repeatedly (which isn’t too hard to achieve at 13,000ft). After they freeze and thaw and freeze and thaw for a couple of weeks, they are often soaked in a stream to leech out many of the bitter flavors. They are then dried in the sun, as seen here. The final product has a texture a lot like Styrofoam. However, it is easily reconstituted for soups, where it adds a distinctive flavor. Different colors of final product are produced by either covering the potatoes during the day or exposing them to the sun. The more sun exposure they receive, they darker their color. Chuño is typically almost black while morayah is a powdery white.

Stone Wall Construction Tricks

Stone Wall Construction Tricks

These indentations are one way the Inca held their walls together. Two U-shapes were chiseled into adjacent blocks and lined up, then molten bronze was poured into the indentations. When it cooled, it formed a ring of solid bronze that united the two blocks. At times, T-shapes were used to the same effect. These pictures were taken in the temple of Qorikancha in the center of the city of Cusco, the capital of the ancient Inca empire. While Machu Picchu has very impressive ruins, in part due to the breathtaking setting, Qorikancha is widely regarded as having the most advanced technological innovations and finest craftsmanship. Since you have to pass through Cusco on your way to Machu Picchu, put Qorikancha on your bucket list as well, and cross them both off at the same time.

Nevado Chicón

Nevado Chicón

Despite boasting an elevation of 17,778 ft, Nevado Chicon is only the 128th highest peak in Peru. The name Chicon is borrowed from the Quechua “Ch’iqun.” Towering over Urubamba, Chicon receives sunlight long after the Sacred Valley is completely enveloped in shadow for the evening. Thus, while the Sacred Valley doesn’t get much in the way of traditional sunsets, watching this peak brightly reflecting the sun’s rays when it’s already dark all around you is a unique alternative. Chicon also offers a very visible demonstration of warming temperatures in the region. In just the past couple of years, the glaciers have retreated several hundred meters. This photo is taken from about 14,000 feet, on the way up to the base of the glacier.

Who is winning here?

Who is winning here?

The answer is the wasp. . . . The wasp is DEFINITELY winning. Tarantulas are pretty common in the Sacred Valley. They like to make their homes in the paqpaq (a relative of agave), and for the most part they are pretty safe there except for one enemy: the tarantula hawk. Ninaninas, as the locals call them, are large iridescent wasps that are commonly seen circling at 2-4 feet altitude over areas where tarantulas live. They sting the unfortunate tarantula, which paralyzes it. They then drag the paralyzed body to their burrow where they bury it along with a single egg. When the egg hatches, the larva slowly eats the living tarantula, sparing its vital organs until last. While the tarantula may look fearsome, it is no match for the ninanina.

Kitchen Floor Symbiosis

Kitchen Floor Symbiosis

Most everyone in the rurals of the Sacred Valley region (and even many people in the towns) have dirt floors. Most families also raise cuy (guinea pigs) that are consumed as a local delicacy. The cuy are kept indoors, usually in the kitchen. In addition to their primary diet of barley grass, the cuy also clean up the variety of peels rinds and other food scraps that make their way to the ground. Their pellets in turn are swept up and used as fertilizer. This picture was taken in the kitchen of an acquaintance in Chichubamba, a community on the outskirts of Urubamba.

Foodies of Peru

Foodies of Peru

If you ask anyone from the Peruvian Andes what their favorite food is, chances are they will answer “cuy” (the local term for guinea pigs). While many people have chickens running around the house, EVERYONE has cuyes, which are fattened up for weddings, funerals, holidays etc. If your cuy was cooked properly, so that the skin comes out crunchy, you will likely enjoy your introduction to this nutritious protein source. Eating cuy that was poorly prepared, on the other hand, is akin to dining on a well-seasoned inner tube. (Please see the photoblog post “Kitchen Floor Symbiosis” to learn more about how cuy is raised.)

Modern Times

Modern Times

“Developing Country” is NOT just a euphemism for “poor.” Peru is an example of a country that is rapidly modernizing. Even though it still has a long ways to go before becoming a fully “developed” country, the leaps in technology are starting to penetrate even the most remote areas. This often gives rise to interesting juxtapositions of culture, as seen here. Many people are surprised to see rural farmers who speak Quechua and still dress in traditional garb conducting transactions at ATMs.

Not Just Potatoes Anymore

Not Just Potatoes Anymore

Say the word “tuber” and the first word that comes to mind for most people is “potato.” Peru is indeed generally recognized as the birthplace of potatoes. But there are many other tubers commonly eaten here that haven’t become so famous. Occa, (pronounced with a guttural “kh” sound) shown here, is typically first left in the sun for a few days. This causes it to lose its bitter flavor. It is then cooked and eaten as a carbohydrate source. The flavor is a lot like a sweet potato with a little added sourness.

Where Cocaine Comes From

Where Cocaine Comes From

Around 2015 Peru finally surpassed Columbia as the world’s largest producer of cocaine, which is made from coca leaves. In the Sacred Valley region, many people chew coca leaves to give them energy, suppress appetite, and elevate mood. Chewing coca leaves is also a remedy for elevation sickness. As such, coca tea is often given to altitude sick tourists when they first arrive in Cusco. If you follow the Vilcanota River down through the Sacred Valley, a little below Machu Picchu you will find yourself entering a region that is warm enough to grow coca. (Around 5000ft at this latitude). Here, a local person near the town of Santa Teresa is drying out some of his crop in the sun. The quantity of coca leaves seen here can be purchased at any local market for the equivalent of less than $1.